This started out as a very succinct post, got complicated fast, and I’m not entirely happy with how it is expressed - but it feels like it needs the discussion more than it needs me to be comfortable with the clarity of expression. I think it describes patterns that are the root of some of the real and really entrenched patterns we have to break to lift our professional groups out of the funk we’re in. So strap in, and as the King once advised Alice - “Begin at the beginning, go on until the end, then stop“ - but I hope you will stop after adding your own views to the discussion - even if they just involve sending me a flaming email telling me you think I’ve got it all wrong (yes, you). So strap in!

The biggest problem records management has are:

1. The way we think about maturity.

2. Our own professional culture.

How hard is record keeping really?

We have legislative requirements to keep records.

We ask people to put their records in a specific place so that they can be managed.

What’s difficult about it?

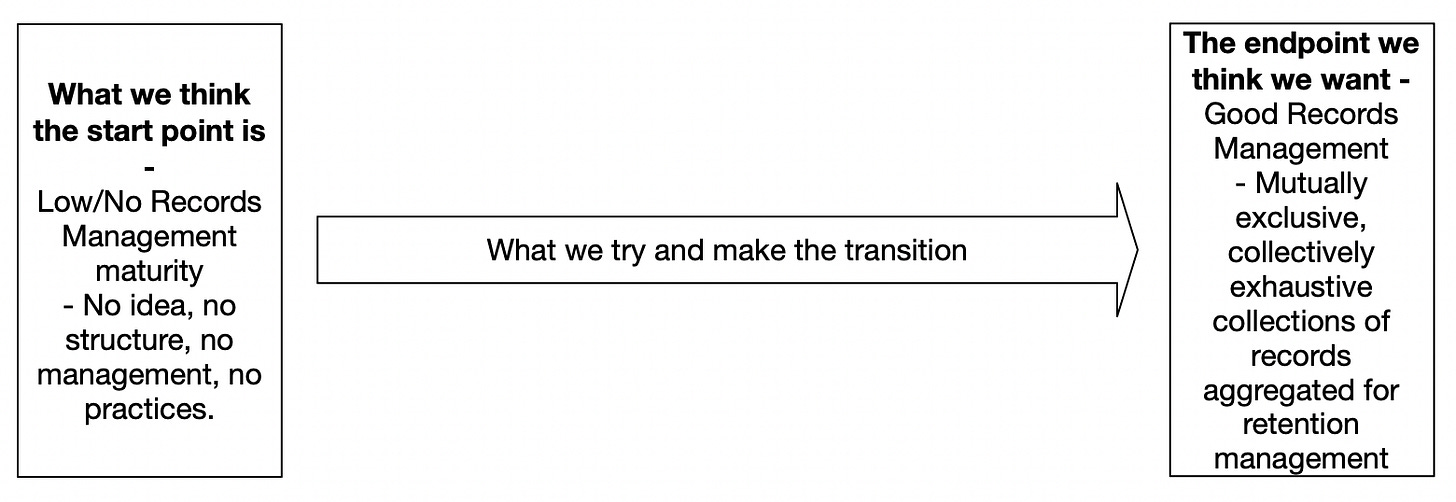

That’s how we think about maturity.

It means we tend to think about maturity like the diagram below.

This makes several flawed assumptions.

1. That we are the only people who manage records.

2. That if records aren’t managed by us, they’re not managed.

3. That if records aren’t structured like we want them to, they’re unmanaged.

4. That the transition is just about how records are arranged and stored.

To me, the journey actually looks more like the diagram below.

The thing that all of records management practice fails to recognise, is that people are already managing their records. They are managing their records according to how recorded information is seen as a source of value in the culture of the organisation. Our typical view on maturity both treats the organisation as incompetent by starting from the view that they are not managing records at all, and ends with us asking everyone to massively over spend on records management relative to how the cultural practices of the organisation value recorded information. The reality of organisations, is that they are all in stage 2 - their practices around management of records reflect their cultural practices related to referencing recorded information. The problem of changing cultural practices, is that current cultural practices relating to recorded information are both a cause of poor quality records creation, and a consequence of them.

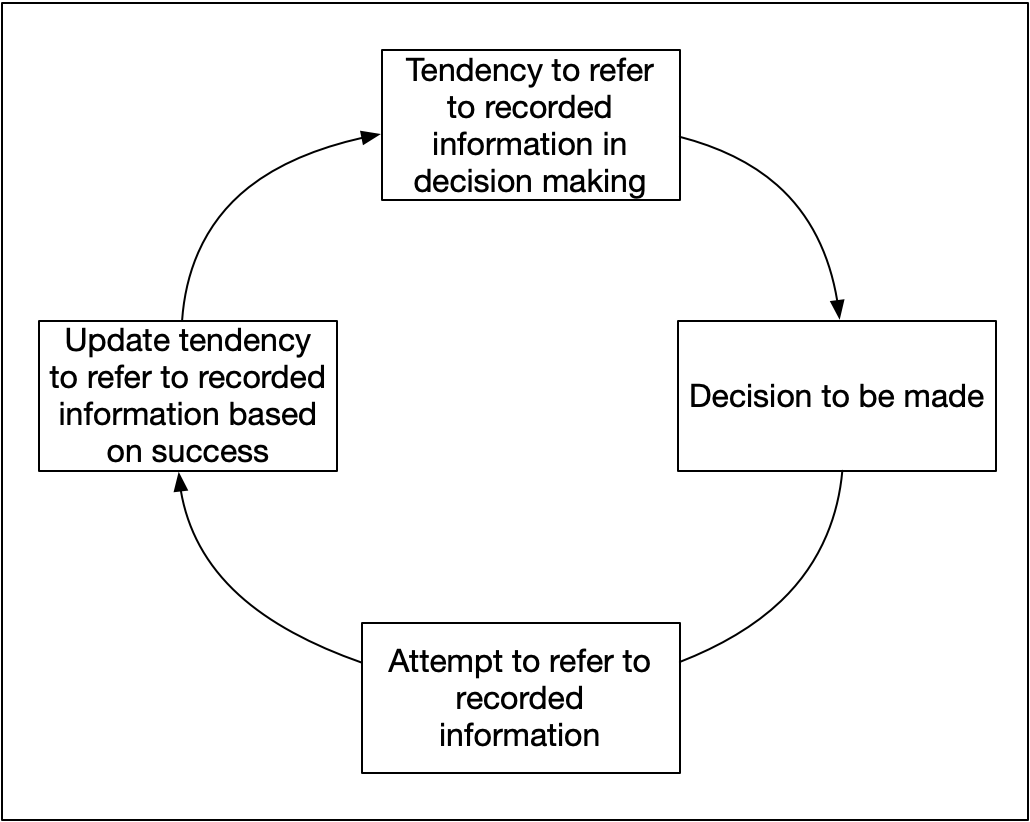

Consider for a moment the diagram below and think about a new starter habituating to your organisation. They come into the organisation with a certain tendency to refer to recorded information when making decisions. When they have a decision to be made, they act on that tendency, if we’re lucky, they attempt to refer to records. Then what happens? Depending on whether they were successful or not, they update their tendency to refer to records as part of their decision making process - either for better or worse. It’s a simplification of the real world, but probably a pretty robust one - a person continually frustrated by records doesn’t keep looking for them, a person who isn’t used to using them, but who finds a source of value and efficiency every time they look for them is going to get into the habit of doing the easy thing pretty quickly.

The problem I see, is that this model holds current practices in place - whether they’re good or bad. I’ve put a four box matrix together below to show how I think this model shakes out depending on polarised combinations of people and information quality cultures.

My hypothesis should be clear - I expect people will habituate to the norm of the organisation they join (or leave). Organisational culture is a very strong influence. The question that I’m interested in, and that I think is key to raising maturity, is in what is necessary to break this cycle.

Ultimately, I think the only thing that breaks it, is individuals with power and authority in the organisation, who can have a longer term focus on raising performance. I’ve tried to capture the reason for this in the diagram below - it’s not perfect, but it’s in the right direction.

The hypothesis in it, is that someone has to create the high quality recorded information before value can be gained from referring to it, until the value is there, the virtuous cycle of creating and referring to high quality recorded information can’t start - it’s just a cycle of spending more time and money creating records for no immediate gain - I think the technical term for this is that it’s a ‘slog’.

There’s a double hit here - creating high quality recorded information costs more than low quality information (as a general rule), and changing the organisation so that it can actually produce higher quality recorded information is more expensive still. That makes the change a serious investment activity, and like all investment activities that involve change, costs will go up initially, and overall performance will go down - which makes it a double hit on an efficiency measure. If we consider the context of an organisation that needs to do this, the problem gets bigger still - it’s likely a low performance, low maturity organisation. This means that a low performing organisation has to be prepared to get a lot worse, to get better. This ultimately makes breaking this cycle the kind of strategic, long term activity that only someone with significant power and influence in the organisation, and political cover outside of it can undertake.

This is a long and complicated argument for a blog post that was supposed to be ten lines - but if you follow the argument, I hope you find something interesting in the idea that low quality records cultures are held in place by the low quality information they produce, and the cultural practices that perpetuates. People are already managing their records - they’re just managing them like people who don’t value information, who create low quality information, and who then manage it like it’s low quality - because it is.

The first mistake we make in trying to raise maturity, is in thinking that people aren’t managing their records. They’re managing them based on the value they place on the records. This might mean that they’re managing them like people who don’t value recorded information, and who (as a result) create low quality information, and manage it like it’s low quality - because it is. This leads to the second mistake we make - which is that thinking people aren’t managing records because they don’t know how to. We think that we can come in and tell people what the best way is to manage records, and they’ll be able to gain all the value that we see is possible from better records management. What we can’t see, is that they think we are insane to spend more money managing their records - because their management practices are calibrated to the value they receive from their records.

To explain it another way, the DIKAR model below, is one of my favourite models for discussing how the quality information matters to an organisation. What the DIKAR model shows, is the link between the quality of results, and quality of data, information, knowledge and actions. Each factor constrains the quality of result that is possible from the following step, add up the quality of the steps, and you have the quality of your result.

When people are used to poor results, or are used to having to compensate for poor quality recorded information with high quality expertise, or really expensive actions, they can’t see why they’d spend money managing their poor quality information more effectively - it just doesn’t make sense to them.

To me, the secret to getting organisations moving along the maturity model, is in finding one or two high power and authority individuals and helping them see how the quality of their data and information is constraining the quality of their results, or requiring them to compensate for it with other factors. Once they understand that, it’s a matter of helping them understand how to invest so they can see improved results - in a couple of years. Once the recorded information they’re producing is gold quality, spending money to manage it like it’s gold becomes an appropriate investment in managing the asset. There’s a pretty significant challenge for records management here though too, and it’s wrapped up in the DIKAR model.

When we as a professional group talk about our results and ability to produce them, everything comes down to metadata - description of the record. As long as records are well arranged and described, our results can be amazing - we can manage huge amounts of records with a tiny resource commitment. The problem though, is that our definition of quality is all about the outside of the bucket - because it’s the outside of the bucket that drives our results. The results that drive our businesses, are all about the quality of what is inside the bucket - not the container, the contents of the container. Until we move the quality of the contents, changing the quality of the bucket won’t make any sense. I have serious doubts though, about whether we as a profession are actually capable of understanding quality as it relates to the results of the organisations we serve. The thing that I am absolutely certain about though, is that understanding how the quality of recorded information drives our businesses is the key to our future success, and understanding how to improve it is key to breaking the cycle our organisations are stuck in and getting more gold value records so that the value of our practices can enhance then even further.

The maturity journey we keep trying to go on, is the one where treat people like they’re not managing their records, and try to move them to the point at which they’re managing their records according to the best records practices. It keeps failing, because the records they’re creating aren’t worth managing. Our professional culture is so strongly indoctrinated about the value of records, that we can’t see when records aren’t valuable, both because we are indoctrinated, and because our definitions of quality are all about the outside of the bucket, when the quality that drives results for the rest of the organisation is about what’s inside the bucket. Until we see this and start working on it, start finding the people with the power, authority and vision that will work with us, we won’t be able to help our organisations get out of the vicious cycle. Our organisations don’t value records because the culture doesn’t rely on records, the culture doesn’t rely on records because it produces records that aren’t reliable, it’s one horribly vicious cycle - and we’re stuck in it with them.

Records and information management is a key to any organization